The Memoirs of Isaac Mathieu Crommelin |

|

01 - My Ancestry 02 - The Duchess of Zell 03 - Musings About Family Lineage 04 - More About My Ancestry 05 - Uncle Joncourt Commissions a Play 06 - My Forefathers 07 - My Early Years 08 - My Youth as a Ruffian 09 - My Father's Gentleness and Wisdom 10 - A Troublesome House Guest |

11 - Lessons in Swordsmanship 12 - Exiled to Live With My sister 13 - Evidence of My Early Business Sense 14 - I Win a Greek Competition 15 - A Trip to Holland 16 - My Education in England 18 - My Astronomy Lesson to King George 19 - I Witness the Execution of Lord Lovat 20 - My Fascination With Magnetism 21 - Restoring Mother's Smashed Heirlooms |

My Ancestry

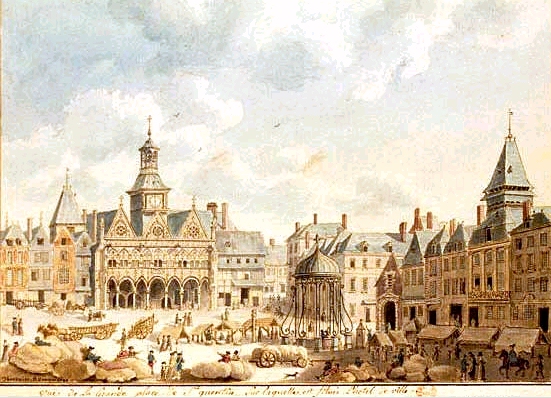

St. Quentin, 1797 (Click to view postcard)I was born in Saint Quentin, capital of Vermandois, on November 27th, 1730 of a father who was universally respected and who left traces in his homeland of his rare merit and ingenuity. My maternal grandfather named Couillette lived in Chauny, and occupied the principal house there. As this city was for a long time the garrison of mounted Grenadiers (cavalry), my aunts took the name of Haute rive ("High bank"). Even one of my uncles, a Garde-du-corps in the company of Charost, and appointed by Catherine, Empress of Russia, to be the leader of the colony of Astracan, carried this name.

Armand Crommelin, from whom I descend, was of old nobility under Henri III. He came from Courtray, established himself in Saint Quentin and, through his ingenuity, brought to it the sources of immense prosperity which my homeland has enjoyed for so long a time.

Careful experiments proved that the soil conditions of his new home were suitable for the cultivation of flax. Thus he formed an enterprise to make fine batistes and linen. Some major obstacles had to be overcome. If the workplace was too dry the threads lost their sharpness, destroying their tensile strength. If it got too damp, the fibres would rot or break.

(2)

To overcome these problems he used hygrometers to control the proper humidity in the workshops. Then he turned his attention to the gluten, (named "parament") used to round off the threads and, with the help of a brush, give them the right consistency.Henri IV, passing by Saint Quentin, wanted to see my forefather's enterprise. He had several conversations with my ancestor, was satisfied with what he saw, and deigned to be godfather of his first child whom he named Henry. This great King then lived at Rembouillet. Thus under the good pleasure of the King originated the fleur-de-lis which the Crommelin family added to their coat-of-arms.

Saint Quentin's factory prospered to an extraordinary degree. Women, girls, old men, and children all found work there proportionate to their ability. The idle became "mulquiniers" (a word which undoubtedly then meant 'weavers'). Misery disappeared and gave place to a good standard of living. And so it is possible for a single man to change the ground of a nation and transform a vast society. The fact is there was hardly a rich family in the neighborhood of Saint Quentin, who did not owe its fortune to the factory - either through the labours of the fathers, or by their association with the factory.

Bleachery, St. Quentin late 1700'sThe mother of my father was a daughter of a famous Doctor Pajon in Romorentin who tried for a long time to bring Protestants and Catholics together. Undoubtedly he would have succeeded if the fanaticism which surfaced during the religious wars could have been neutralized. Doctor Pajon is the author of several esteemed works, one of which was a Treatise on Prejudice.

The Duchess of Zell This admirable gentleman had a niece named Miss Dolbreuse, a cousin of my grandmother. His reputation and her rare beauty drew the attention of the Duke de Zell, so that she became a Lady-in-waiting of the Duchess.

(3)

The Duke became amorous toward her but encountered resistance which he did not expect. Miss Dolbreuse left secretly but, motivated by a letter to the Duchess which explained the reasons for her departure, she was immediately recalled whereupon the Duke said to her, "Because you are a lady and a girl of honor, I promise to respect your virtues."Eventually the Duchess died and left two children. Then the Duke (always a lover) suggested to Miss Dolbreuse that she marry him of the left hand because, in Germany, they are very particular about alliances because of the districts of nobility. I read in Orleans Miss Dolbreuse's letter to my uncle, the Doctor Pajon, and I saw the answer of my uncle to his niece. He wrote "that the marriage of the left hand was worth that of the right hand in marriage, and the only difference related to title: that she would rightly be the wife of the Duke but not a Duchess; that there would be nothing in her marriage that should bother her conscience and that besides, he had displayed discretion and wisdom." These papers in Orleans belonged to Mister Pajon, my relation, a professor of law who didn't think it proper to give me a copy.

Miss Dolbreuse married the Duke of the left hand and had two girls. After the birth of the younger child, the Duke lost his two children from his first marriage. Wanting to settle the standing of his second batch of children, he sought, for his wife, the title of Princess of the empire. He obtained it. Then the marriage of the right hand was made with solemnity, and Madame de Zell became a Duchess. Later both girls married - one to Frederic I, Elector of Brandenburg, who became king of Prussia in 1706. The other one married the Elector of Hanover who became George I, King of England. I would have kept silent about this fact, if there were any doubt that I was the great-grandson of Doctor Pajon, and if I hadn't read the original details myself. Besides, wasn't she the niece of a grand-relative to my father? She was his grand aunt which is no small thing.

(4) Musings About Family Lineage

As for kinship only time is of consequence because if my father were still alive today he would be 121 years old, and I would effectively have 78 of those years. There are few bourgeois families which have connections to two crowned heads but I see nothing very glorious in that. Girls of financiers and grand families have given birth to Lords or some of the most mean villains. There are always upstart sovereigns. "The first one who was king was a happy soldier".Sforce were linen shopkeepers in Florence and thus it is easy to see Highnesses among which parents were born in poverty. But let us calculate a moment. Let us marry boys 23 years old, and girls of 17, the average is 20. A century therefore produces about five generations.

I have an older sister who saw her great-grandparents and who now is great-grandmother to a nubile girl. She thus could see eight generations and, as a consequence, the existence of 256 grandfathers and grandmothers. Now let us see if this is correct:

8- The eighth generation has a father and mother - 2.

7- This father and mother each had a father and mother - 4.

6- These four also had a father and mother - 8.

5- These eight had parents totalling - 16.

4- These sixteen had parents totalling - 32.

3- These 32 ditto - 64.

2- These 64 ditto - 128.

1- These 128 ditto - 256.If we do not deny that my father and mother gave me four grandparents, these four gave eight great-grandparents (bisayeux) these eight, sixteen great-great-grandparents (trisayeux), then the doubling relationship is evident. So, by going back 400 years there would be 20 generations and some one million forty two thousand, one hundred and ninety-six ancestors. Now if I add 200 years to obtain 30 generations, I shall have one billion, sixty-seven million, two hundred and eight thousand, seven hundred and four ancestors.

(5)

These are direct ancestors so that if only one were removed from this number, it would be impossible for me to exist! We shall observe that if I counted the uncles, the aunts and their ascendents, I would have over 600 years 6 times more ancestors than there are people on the globe. Then we add to that accidental mixtures: big Lords who are the offspring of their servants; servants who have big Lords for fathers! The Turkish sultan is always the son of a beautiful slave; Peter the Great married the woman of a drum; Louis XVI was allied to commoners by Gabriel d' Etrés, of whom a girl married the Duke of Savoy. It is believed that Louis XIV was not a son of Louis XIII. In general the great, the blood of whom was not mixed for a century, are very ugly because everything degenerates, in the animal kingdom as it does in the plant kingdom. That's why pygmys who do not cross their races are usually small and stunted, but the beautiful Jewish women, who understand this, know the way to prevent this inconvenience.More About My Ancestry Now I return to my family.

My paternal grandfather was Pierre Crommelin. He was the richest private individual in Vermandois. He hired an inhabitant of Languedoc to be his clerk and gave him one of his daughters in marriage. They had no children. Pierre Crommelin, born Protestant, enjoyed the family status (registry) granted by Henri IV. The repeal of the Edict of Nantes gave birth to persecution and scattered my family. Those who fled to Holland, entered the judiciary and military profession. The brother of my father, was the general Crommelin whose regiment bore his name in the battle of Fontenoy.

Battle of Fontenoy, 11 May 1745(6)

The States of Holland gave him the governorship of Gertruydenberg, and appointed his son to that of Surinam.Uncle Joncourt Commissions a Play I am related to a Crommelin who is now one of the leaders of the States of Holland and one of my relations (Henri) who carries his name, was the chief magistrate of Haarlem where it is stated on the baptismal font that he was the last Stathouder. His schoolteacher was a mister Joncourt, my uncle, a husband of a sister of my mother. [A rather naughty epigram was made about Miss Couillete's marriage to Mr. Joncourt.] The father of this prince was hunchbacked. One day I attended a lecture of my uncle, when the Stathouder tiptoed into the room holding a finger to his lips. I remained quiet. He stood behind his son, listened for four or five minutes and said, "Joncourt, I am very satisfied with your way of educating. Please continue, and we shall have success." Then I was presented as a nephew and a 'French poet'.

Now I shall relate what gave rise to the fancy title "poet" with which I was honored but really didn't deserve...

I had dined the day before with the Joncourt family. A young Parisian who, claiming to be a poet, read us a sort of idyl of his composition in which there was an invocation relative to the promenades of a young prince. I asked permission to read it myself. My uncle perceived (perhaps by my furrowed brow) that I wasn't too happy with it. After coffee he took me aside and said, "The idyl doesn't please you, I'm sure of it. Please speak frankly." I replied, "Before answering you, I have to know whether you have a vested interest in this production." - "Yes," he replied, "In fact I'm the one who commissioned it." - "In that case, it isn't fit to be presented without some revisions; I see errors and nonsense in it." Mister Joncourt called the young man, and led us to his study.

(7)

"Now, my dear nephew", he says to me, "explain without hesitation - this gentleman is my friend. Show us the nonsense which you just spoke to me about." - "Well," I replied, "since you insist, here is one: Roses charming the senses with the perfume of its flowers.""A flower does not consist of flowers. Certainly the gentleman means to say: Roses charming the senses with the perfume of its blossoms. Though I agree it is pretty much the same thing." I also pointed out a few false rhymes and prosaic verses. So the piece was retouched, presented, and became quite a success. Criticism is easy, but the art is difficult. Losing sight of this truth, my uncle still thought quite highly of me. Oh, I know how to write poetry, but I'm certainly no poet.

My Forefathers Now I return to the emigration of my family.

My forefathers who took refuge in Ireland, established in Lisburn the magnificent linen factory which still constitutes the principal wealth of that country. One Crommelin married the lord Montgomery, a descendent of the one who, in a tournament, had the misfortune of killing Henri II of France.

Those who sought refuge in Geneva were from father to son professors in history. The last of these Crommelins preceded Mr. Necker in the diplomatic corps and his father had the distinction of helping the great Rollin in his ancient history as compiled in his 'Traite des Etudes'.

My father, Jacques Samuel, raised in Holland, had a taste for travel and a flair for languages to a high degree. He spoke almost every European language with incredible ease. This was a knack he picked up in Italy - in the city of Livourne, if I'm not mistaken. The wind had been contrary for a considerable time; vessels of many nations were waiting for the favorable moment to enter port.

(8)

When it arrived the port officials boarded the ships to question the captains, but with all the activity happening at once they lacked interpreters. My father served as the translator for all the nations. Magistrates and officials offered him due compensation for the mass of interpreting which he performed, but he politely declined. However, he was obliged to accept a meal and a small painting by Vandyk of which I will perhaps have occasion to speak further.Meanwhile my paternal grandfather, Pierre, passed away while his son (my father) was away travelling. The clerk from Languedoc which my grandfather had hired by this time had become an associate and he conveyed to my father all the matters of business. When my father arrived home he was told that his association no longer existed. When he demanded to have it restored he was paid off in bank bills, I.O.U.s and drafts. Meanwhile the former clerk had now become boss of the house of Crommelin, along with four of his nephews from Languedoc and he eventually left his oldest child an immense fortune. He married the richest financier in Paris, loaned considerable funds to his brothers, who, having applied themselves also built large commercial houses.

As there were reports of kinship between the uncle of the four brothers and myself, since he had married my aunt, I am related to grandiose French families who prefer fortune to titles. Here is an example of the kind of mixtures I spoke of earlier.

[Note: Since Catherine, the daughter of Isaac's grandfather Pierre, married Etienne Fizeau, a partner with his father-in-law, it may be that Etienne Fizeau was the unscrupulous clerk who eventually took over the House of Crommelin.]My father, still young, returned from his travels to find his affairs in turmoil and to a very reduced fortune. He then married and in his own name formed a commercial house that became a success. But following that, never was a man more unfortunate. His own paternal aunt managed to lose for him more than a hundred thousand francs in London. Large capital gains from well thought-out investments were suddenly seized by the English in 1739, without any declaration of war, thus reducing the major part of his fortune.

Then one of his associates, established in Cadiz, loaded himself up with a large assortment of merchandise, died as a young man and left his fortune to an adventurer who seized ownership of all the stores. No one was paid for the goods and loud was the noise from all those who had lost out. In France one would have recourse in such matters, but in Spain scoundrels are protected.

My Early Years

(9)

Having made the acquaintance of my ancestors, I am going to speak now about myself. Pardon me, readers, if I let escape from my pen some traits of my childhood.Born very frail, at 7 years of age I did not know how to read; for me it was a very big effort; at 10 I ran like a deer, climbed like a cat, swam like a fish, and I did many pranks. These little details sound inconsequential, perhaps, but:

1. My life is not that of an illustrious man

2. I do not write for the public

3. Some traits bear the stamp of originality, and moreover, they have a connection with the opposing characters of my father and mother: the one was a wise, indulgent philosopher, a clear thinker and observer who, having studied people, understood their tastes, passions and inclinations and the nature of children. He raised them with ingenuity, did not oppose them, and rarely was wrong with his intuition. On twenty occasions he proved to me the accuracy of his judgement.My mother, on the other hand, was of a stern disposition. She displayed the manias of her times: she gave little regard for the need of exercise and believed in the efficacy of severe punishment. Usually she meted this out in the morning. One day I decided to open an upstairs window and hang from the eves. My father saw me dangling there and, arriving trembling and pale, passed his belt under my arms, then called for help. The danger which I had put myself in was a lesson to my mother, but she had recourse to another way of punishing me by involving my Latin teacher.

A sort of instinct made me suspicious and the idea came to me to buy an image of Saint Claude and stick it in a place where Mr. Claude Martinsort would be sure to see it. Indeed, after the class, he asked me to stay behind and thus miss part of a ceremony. I then pointed out his patron saint and begged him to respect it. He then took a quill pen, wrote something, and laughingly said to me: "Here, take that to your father!"

(10)

But I knew that my father would laugh a lot. The pupils called me "the saint" after that, but after some incidents the nickname did not stay with me for long. I was supposed to receive a brilliant education but I took to it rather badly. Because I habitually didn't pay much attention I spent a lot of time standing in the corner. While my companions enjoyed themselves in the daytime doing normal lessons, I was made to learn a section of catechism and read about true merit. That's what turned me against merit and virtue.My father was most indulgent when complaints were made about my behaviour. He said simply, "The wine has to ferment before it becomes desirable" - a philosophical word which was typical of him.

I had a brother who was fourteen months older than myself. He was less mischievious than myself and endowed with a most vivid imagination. Strong, firm and brave, he never retreated. His childhood and youth are marked by a singular notable quality: he projected a kind spirit and generally had a unique character which widened his circle of friends because it was impossible for him to be angry. But in our adolescence we were the terror of our companions because we stood up for each other. Neither of us could be attacked in isolation. We had the same education and the same teachers, but our tastes, our knowledge and inclinations were completely opposite. This suggests to me that certain faculties are hereditary as well as certain physical features. My brother resembled my father in his calmness of spirit while I took after my mother having inherited her irritableness.

When a woman of wit and learning marries an imbecile, all the children will have the traits of the mother and be intelligent; those who take after the father will partly share his intelligence. Every sex thus has its primitive germs, and these germs have a pre-existent organization. It defies explanation, but the secrets within a generation, cannot be

(11)

revealed, and the facts are surer than the reasonings. Here are two eggs. They are similar; I break them; the microscope which enlarges a million times does not show me any difference. However, one would have produced an English cock of battle, with an imperial head, decorated with feathers and with varied traits, armed with ergos of 18 lines, while the other would have produced but a small, shy, white chick.My Youth as a Ruffian Here are some of my father's traits which reveal his character, and the peculiarities which were appropriate for him. Seemingly calm in appearance, he became violent when his patience had run out. I would compare him to a rifle which explodes if you put too much powder into it.

One day a large gathering of ruffians met to plan a fight which was to take place in the ditches of the city between two gangs, one of which I was the leader. The rendezvous was in a vast storeroom filled with bundles of sticks where 20 of us upstarts were to choose weapons. Then my father came to find us. Without so much as a word of reprimand he asked us all to follow him. This happened to be a day in which my mother was hosting a large gathering of her own. Bidding us to enter and with a tone of the most affectionate politeness, he said, "Ladies and Gentleman, I have the honour of introducing you to my sons and their friends." Now these were the children of artisans in leather aprons and scruffy characters all dressed in rags. The scene made many laugh while my mother's face reddened. She didn't think too much of the joke. However the lesson was learned and since that time all gang fights came to an end.

My Father's Gentleness and Wisdom Another time I was in charge of treating all my friends. I chose a storehouse filled with apples and other fruits. Unfortunately it was locked and bolted, but by climbing through a narrow hole and over two walls I managed to gain entry.

(12)

I filled my shirt with the best fruit. Coming down again, I felt a hand reach out to support me. When I landed, I found myself nose to nose with my father who, with an icy look, released me from my apples. "I see that you have chosen your fruit well," he says quietly, "but they aren't ripe". He gave two apples to each of my companions, then addressing me he added, "Since you went to all the trouble of getting them, it would be wrong to deprive you of your share. Here, have some." The next day the hole was blocked and my mother ignored my naughty behaviour.This father of mine who was so good, so indulgent, and who reasoned so wisely with those of all ages, was extremely shy. I recall that when Louis XIV passed through St. Quentin on his way to conquer Flanders, Mr. de la Billarderie, officer of the guards and governor of St. Quentin, came to find my father and said to him, "All the citizens turn their eyes to you to respond to His Majesty's questions about our fair city of Saint Quentin. Follow me, please, and I will present you to him."

My father responded to the king with the utmost presence of mind, giving him a sound overview of the factory, and even details which required basic preliminary comprehension were explained so clearly that everyone understood perfectly. The King admired the precision of his ideas, the elegant simplicity of his language and his candid manner, but the effort my father made to overcome his nervousness made him physically ill for several days.

A Troublesome House Guest By this time the whole of the king's retinue had passed through St. Quentin. We were given the Prince de Craon to billet in the living room. He slept in an exotic bed from India; great courtesy and particular consideration was to be extended to him. A few days before, the police of the guard arrived and an officer of this body appeared with a note for lodging the prince and his servant. Father led him into the room intended for the servicemen, showed him

(13)

a spacious cabinet for his servant, a stable for his horses, and asked him to arrange all the things which he would need."That is all very good, but I also have a nephew," said the Prince when he arrived. - "But here is your note for accommodation. It says nothing about lodging two persons, and it isn't customary to insist on two beds." - "Customary or not, you will accommodate him as well." - "I wish to point out to you, sir, that it isn't me who is under orders here." - "In that case, I am going to stable my horses in your living room." - "I will not oppose that, sir, but I shall resort to law in this matter. Besides, you are now in your quarters and I shall go to mine. Let there be no more communication between your quarters and my house."

Then the nephew, a fourteen-year-old youth who was in the courtyard, insulted my father and made an obscene gesture. - "If you had a beard, young man, I would go find your superiors and have you punished...but you'll not offend me again." The scoundrel then walked up to my father and grabbed him around the neck. Seeing this happen through the dining room window, I flew to a sword that was hanging on the wall and swept down on the young man shouting to defend himself. My father, who could not contain me, grabbed me by the hair and pulled me away.

Half an hour later several officers of the staff arrived. - "We know, sir, the character of the officer who is lodging with you, and the municipality knows you well. We've come to ask for your account of what happened and we will believe you." The tone of my father and the innocence painted on his face made the officers shrug their shoulders.

Then the nephew appeared and I as well. He accused me of attempting to murder him, but I said that he had grabbed my father around the neck and that, with sword in the hand, I had shouted to him to defend himself. The officers looked astonished. - "What, you raised your hand against this gentleman?! Go, you rascal, and wait for us to take charge of you!"

(14)

"Sir, please accept our apologies," and they went out.Lessons in Swordsmanship At an early age I was put in the hands of a fencing expert to help me grow up. Although this was a good plan, Mr. Constans as a swordsman emphasized head knowledge too much, speaking to us primarily about his exploits and about the sense of honor attached to vengeance. These lessons, in the heart of Picardy returned a few lively pupils.

One day when I was in the classroom, I blew on a bugle of the regiment of Clermont-Tonnerre, whom we all admired because he was a good musician, accommodating, and honest. Then a cavalier arrived who at the time was the butt of satire and jokes because he had just married a young lady who had recovered from (?) for the second time. According to custom I presented him with a foil to cross whereupon he undoubtedly took me to be a novice. He replied that he didn't duel with just anybody.

Piqued by his remark, I commented on his unceremonious marriage. That was sure to get him going. Imbued with Mr. Constans's principles, I seized his foil which was in a corner of the room, and I beckoned for the cavalier to follow me. It must have looked crazy because I looked like only a pupil. We took a detour toward a street where I was going to draw my sword when suddenly Mr. Constans, who had taken a shortcut through a garden to intercept us, opened a door and revealed himself. Speaking to the cavalier he said, "You have offended my pupil who is better than you, and you have offended me because, when you presume to be what you are not, then weapons are quickly resorted to. This deserves a correction, and it is I who shall give it to you. Don't be afraid - you will suffer only slightly." In the end no fight took place. The aggressor went off and things remained the same. But from this time onward

(15)

it was expressly forbidden for me to wield a sword and also to never again take lessons in the use of weapons or even to enter the classroom. And to help me forget these martial arts, I was sent to Sedan to live with my sister who was married to a merchant in this city.Exiled to Live With My Sister My brother-in-law had some spirit, but being an only son he had been raised prim and proper, and therefore never had been naughty himself. That's why he had little patience for those who displayed a naughty streak.

At this time freemasonry (franc-masonry) existed in all its force. These masons wore a small trowel of silver or gold hung on a blue ribbon. All the sons of freemasons also had these and this distinction pleased me a great deal. But those of my friends were all made of tin or lead. Well, I wanted one made of silver, so how could this be done? I took some silverware and filed it down. A small silversmith gave me a bone and sand, and in a melting pot I made a mould. A brewery where I made frequent visits for free provided me with a furnace. In this way I made my trowel of a quality which surprised many. Unfortunately it was discovered where I had obtained my raw materials and, although the product of my labours was exemplary, I was put on bread and water for 8 days and relegated to an attic near which cats held forth their nightly sessions. But my sister and her chambermaid brought me consolations.

I must not forget to mention that my brother-in-law gave a big meal to the principal officers of the garrison. Tired of my captivity which lasted for several days, I dared to make a petition in verse patterned on one of Mr. Drelincourt's pious sonnets. I attached the petition to the neck of a cat which eventually returned to its owner. Later the chambermaid carried the agent into the room followed shortly by five or six officers who indeed wanted to see me liberated. Without further ado they led me to the supper table where I dined sumptuously and since I was well-supported and even

(16)

stimulated, I unburdened my grievances while the merry persons sided with me. Apparently I had pleased the officers because whenever I walked past their cafe, they let me in to chat with them. Here is the petition which I delivered via the cat. I would have forgotten about it if my sister hadn't saved it.I do not make resistance

If I have to be locked up

It is a hard punishment

But I believe I deserved it

I put myself on my knees

Begging you for mercy

May your nature so sweet

Find my submission agreeableToday a similar rhyme coming from a twelve-year-old would have absolutely no merit, but in my day the notion of writing poetry did not occur to a twelve-year-old.

Neither my brother-in-law nor my sister knew any foreign languages, so when they wanted to communicate amongst themselves without my being able to understand, they used a sort of jargon which I came to know as well as they did. By this means I had secret knowledge of all that concerned me. When I left to return to my father's place, I spoke my farewells to them in their own gibberish. - "Kid brother," says my brother-in-law to me, "you really are a little rascal." - "Not at all," I replied. "It was important that I keep my secret for stronger reasons than yours because each day I could have been taken advantage of!"

I returned to Saint Quentin somewhat chastened because my sister led me into her social activity. To settle me down I was made to do some embroidery and it was observed that my floral bouquets had a great deal of relief. My father drew very well. My brother and I inherited this talent, but endowed with a stronger imagination than mine, my brother sketched without enthusiasm and thus was unable either to copy or finish anything. There was some originality in his ideas and no shortage of ability, but during his lifetime he never finished a single drawing.

(17) Evidence of My Early Business Sense

I was a little more than fourteen years old when a German correspondent of my father named Goring arrived at the house. He was rich and a big connoisseur of paintings. When we showed him something he liked, he used to say, "I accept. It is for my grandson Jean Frédéric." He accepted the small Vandyck painting given to my father by the municipality of Livourne and also a substantial quantity of prints which belonged to me. He intended, "to settle by a considerable commission, but found no business acumen in me." So I promptly went to my father's desk where I made out a fifty-ecu letter of exchange to my order, payable on demand, and I presented it to the German. "You agreed, sir, to accept my prints. I hope that you will accept this small draft". Having at first laughed at my idea, he had me prepare a receipt and paid the sum. This pleasant mercantile anecdote made the rounds. Never had I been so rich. This fortune gave rise to an agreement within our family.My mother offered me an ecu a week, provided that I do my chores and pay a nominal sum for my keep. She did not lose in this transaction, but the ability to satisfy my wants while also saving money instilled some business sense in me. In other words I became thrifty. I believe the best way to impart to a young person the fickleness of money is to let him handle a little of it.

I Win a Greek Competition My taste for military service was well ingrained. In fact my uncle, General Crommelin, wanted me in his regiment. I was never able to undertand why my father refused this opportunity. Rather inconveniently I was put back in school at the age of fourteen under my former professor Claude Martinsort. He was too weak for my liveliness and my age. To please the parents of his pupils, he proposed a competition and a prize for Greek.

(18)

The fact is that he had taught us only the names of the letters of the Greek alphabet, a declension and, I believe, a conjugation. However the challenge was to write an essay. I had a bright idea which I turned into a success. I simply collected Greek letters at random and separated them to form things which looked like 'words' to the eye. Then for sentences I simply strung these 'words' out by putting spaces between them to form 'lines'. Well, my companions produced nothing, so I won the prize! Then I was warmly praised for my proficiency in Greek! This sort of reputation is not rare. In class never bet against the pupil who shows the most temerity. The real thinkers are usually always shy.A Trip to Holland About this time my father made a journey to Holland and took me with him. One of his English correspondents met him in the street, drove him to his home and offered him a bottle of Claret (Bordeaux). Bottles rapidly became empty in the course of the discussion but nobody seemed to notice. The Englishman got my father quite intoxicated. While passing over a bridge in Rotterdam, my father says to me; "Give me an arm - this Englishman surprised me; I drank more than I should have. My son," he added, "you saw me under the weather today, but not beyond reason. You can now get tipsy twice without having me get angry, but in the course of your life, please remain as sober as I have been."

We then went to Leiden where I saw a very extraordinary thing. One of our relatives, a large, active lady, was 100 years old. She had married at age 14 and had twins who were only 15 or 16 years younger than herself. Now these three women were tossing an ivory ball to each other and that made me laugh despite winks from my father. I'll never forget what this 100-year-old woman said to me in a firm voice. "My friend, you shouldn't laugh at old people. These two women whom you see had a lot of spirit but reverses in life hastened their decline, otherwise they are still in their childhood. The same fate awaits you perhaps, and then a stunned young person will laugh at you."

(19) My Education in England

A short while after my return to Saint Quentin, I left for England via Holland. I came down to Haarlem and the home of my great-uncle. Waiting for me was an Englishman who was to take me to London. One morning he called me into his room and asked me if my dad was well-to-do. I replied that my father was a wise man and that he had neither too much nor too little. "Well! I'm going to give you a present. Are you a good mathematician?" - "Yes, I'm fairly good at arithmetic." - "Fine, then do this addition for me." - I did it. - "Here is the sum and my calculation." - "Well, here is a shorter and more accurate calculation for you." This was the 'present' which he intended to give me. As a pupil I found him somewhat narrow-minded, but since then I have come to appreciate the value of his 'present'.When we arrived in England, fate gave me for a schoolmaster a man of letters named Burgh who was building a boarding school. I was the only one there for the three months following. I learned English quickly and drew from my schoolmaster an uncommonly good education. Without interruption I experienced the joy of learning. In fact, a single incident created in me this desire to learn. I dined at the home of a correspondent of my father. His son, a young man of my age arrived. This young man conducted the affairs of the enterprise with a great deal of intelligence. He made all the negotiations for the stock exchange, made the purchases of the company from India, and sold government securities with profits to himself. Next to him I was very small by comparison. The desire to better myself burned within me from that moment on. I devoured Chambers, the English encyclopaedist; I made a passable English grammarian; I went through Newton, commented by Maklaurien; I clung to the astronomy of Keil and the physics of Desaguillers etc. I never left my room without a copy of Price - later to become doctor Price, the very stubborn political author.

(20)

It is him who gave me the best swimming lessons. This friend got me accustomed me to breaking the ice on the surface in order to enter the water at the end of November. It's possible that I can attribute the force of my temperament to these cold baths.

My Astronomy Lesson to George III, King of EnglandMeanwhile Mr. Burgh continued the preparations for his boarding school where astronomy was to be an important part of the curriculum. He used a round table to portray the planetary system. The sun was at the centre and proportionately smaller globes represented planets and their satellites - all at their relative distances - and wings, more or less oblique, dramatically showed the planes of their orbits. I worked on this machine a lot to educate myself, to be useful, and for personal development reasons because, having been born skillful and with an eye for precision, I relished the neatness and exactness it required. One of my friends, a promoter of Mr. Burgh, mentioned this table to the Prince of Galles, the son of Georges II, grandson of Miss de Dolbreuse. He wished to see it and sent a page to ask the author to have it transported to the palace of St. James on a given day and to give a demonstration of the celestial bodies to his sons, the princes.

"Crommelin," says Mr. Burgh to me, "you will come with me and carry some of the instruments. And I shall say that the execution of this machine is your work." We went to the court on the appointed day and the Prince of Galles, wearing a housecoat from Peking, came into the apartment of the Princes. While he honoured my schoolmaster with small talk, I drew the universe out of my pocket and arranged the celestial bodies in their proper places, but not without some minor alterations by the princes whom it was necessary to tolerate and show respect.

Mr. Burgh showed them the principle behind the seasons and moon phases; the cause of

(21)

solar and lunar eclipses; the effects which produce the obliqueness of the ecliptic on the equator; and he answered with skill the questions which were put to him. The elder of the Prince's sons posed a question about the moon. Said Mr. Burgh: "I call upon your Highness to allow my pupil, the young Frenchman, to answer this question. He has been in England only eight months, and upon arriving he didn't know a word of English."I demonstrated the change of the phases of the moon, what causes two eclipses to occur about every 29 days; I showed that the moon was the satellite of the earth; that it is subordinate to the earth; that the moon has two movements [one of rotation on its axis and the other one of revolution around the earth]; and how the earth and moon interact in a lively manner[through gravity causing the tides]. The Duke of York, who since childhood had white eyebrows, asked me why the sun rose and set. I placed a point on my small earth and asked him to suppose that this point was a man. Then, making the earth to rotate on its itself [on its axis], I demonstrated the mechanism which caused day and night, etc. etc. The Prince of Galles, who spoke rather poorly said to me, "Very well, my boy, your progress in science and in the English tongue is a credit to both your intelligence and your schoolmaster." I thus pride myself in having given a lesson to Georges III, King of England and his brother, the Duke of York.

I Witness the Execution of Lord Lovat

Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat by HogarthIt was about this time that Lord Lovat, the Scot, was beheaded for the crime of high treason [on April 9, 1747]. He was an 80 year-old man, who treated badly his creditors. Here is an amusing anecdote about this lord. Two traders arrived one day at his estate with a grandiose business proposal. They were received, entertained and invited to stay overnight.

During the night the lord ordered two gallows to be erected

(22)

below the window of the two traders. Hung from the gallows were two mannequins. At dawn the two dinner guests got up, saw the spectacle and uttered a cry of dismay. "It's nothing, my friends," says the lord to them. "Two scoundrels came by to ask me for some money. Since I have none I decided to hang them." These two gentlemen took the hint and promptly left, taking their grandiose sales pitch with them.A disastrous event occurred during the execution of this lord. It seems fate is fickle because if I were to have twelve francs in my pocket instead of six, I might not be alive today.

All the open space at the Tower of London was filled with galleries (bleachers) for spectators. I too wanted to go up there, but was asked for half a guinea. Since I had only five shillings in my pocket, I was obliged to remain below where many people were crowded together. Lord Lovat then arrived in a coach all draped in black. He mounted the scaffold, put on his glasses, and read the inscription on his coffin. Then he took the headsman's axe and felt the sharpness of the blade with his thumb. At that precise moment the wooden galleries began to collapse and hideous cries of alarm filled the air. Before dying, Lord Lovat himself witnessed the deaths of numerous people while the total of injured spectators was considerably more. The lord was a very big and tall man. I recall that the head was received on a piece of scarlet fabric.

My Fascination With Magnetism Shortly thereafter Mr. Fergusson, a famous astronomer, invited scholars to come and see a machine of his invention which demonstrated the cause of certain irregularities in the movement of the moon which occurred in August, resulting in what the English call the 'harvest moon'. I was allowed into this assembly with one of my relatives, given under the auspices of Lord Beaustere who,

(23)

having been welcomed by my father after the battle of Fontenoy, was honoured by his friendship. Now, my young relative happened to be a derisive and quarrelsome individual, and was usually given a wide berth even by his friends. He sees in the room a small man of plain appearance, approaches him and begins to ridicule him. This little man happened to be Mr. Fergusson, and this is how he took his revenge. Instead of covering us with shame, he addressed us and asked us to approach because we appeared to him to be young people full of merit. I cannot think of a nobler line of moderation than the one he used. When it was time to go, I was one of the last ones to leave, and with tear-filled eyes, I embraced him. He seemed sensitive to this gesture and welcomed me with kindness.I wanted to have one of the artificial magnets about which much had been spoken. He called over Mr. Canton, author of the discovery, who placed before me two pieces of steel which exhibited strong magnetic attraction which he sold me for a guinea. This attraction is the effect of friction, and one can induce magnetism into a clock spring, a shovel, or a pair of tweezers. To do this one must face north and rub the steel outward from the centre in both directions. Doing this will create two poles and an equator in the magnet. Then if you join together several blades by uniting similar poles, you will have a very strong magnet.

I spent eighteen months in England with Mr. Burgh, and it is there that I developed the philosophy, which saw me through my life's reverses, misfortunes, injustice, and which I enjoy into a very advanced age.

Restoring Mother's Smashed Heirlooms Here are some vignettes of my youth which I should relate in my memoire. I was eighteen years old, sick with a fever and with medicine in my stomach when, at four o'clock in the morning, I hear in the kitchen

(24)

a very violent crash. I go to investigate and see three petrified maids, a table with soil and a shattered set of very valuable porcelain dishes. These were wedding presents, heirlooms for over one hundred and fifty years, and handed down from father to son. My father leaps from his bed and appears in the kitchen. - "What happened?" - "Sir, the rope of the folding table broke." - "It isn't your fault as I can see, but the damage is enormous and my wife placed great value on this set of china. I don't see a single piece intact." - "I don't claim to be able to repair this accident, but nothing will come of it if Louison can prevent my mother from getting up before ten o'clock." She did not ring her bell, consequently my mother did not wake up at her usual time. - "Now, go to your train; if you succeed, I shall keep silent."In Saint-Quentin there was a very skillful dwarf who had a glue for china of surprising strength. I sent him over to look at the damage, and we turned on several stoves. I asked for my commode and while returning for my medicine, I collected the fragments of every broken item while the dwarf did the repairs. When sounds came from my mother, we deceived her as to the time. Finally all the pieces were lined up again in their usual places on a particular buffet and the amazing thing about this story is that my mother never knew that anything had happened.